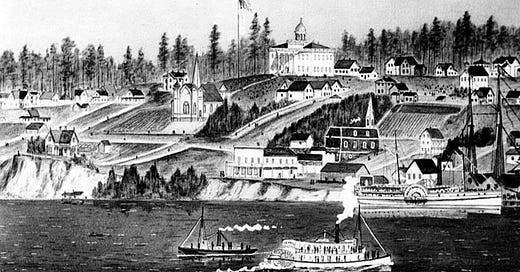

Seattle waterfront circa 1865 vicinity of Pike Street featuring 1861 Washington Territorial University (Undated photograph of unattributed illustration University of Washington Special Collections Seattle Photograph Collection Item SEA1386)

Established 1852, Seattle was still a small village when Emanuel (or Manuel) Lopes (1812-1895) arrived in 1858. Sadly, no image of him survives. The United States Census of 1860, Seattle’s first census, counted 302 residents throughout King County, most in Seattle. We know Lopes was born in the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands. What is not clear is if he was born slave or free. At some time during the 1830s or 1840s he jumped on a New England whaling ship based out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Lopes married a woman named Susannah Jones. They had a son. Both died of unknown causes. This tragedy may have precipitated Lopes’ move to the West Coast.

In Seattle Lopes opened a barber shop (reputedly with the first barber chair brought around Cape Horn) and restaurant on the east side of Commercial Street (today’s First Avenue South). Both businesses proved popular with Seattle’s white residents. Lopes repaid Seattle’s support by providing meals whether the customer could pay or not.

A booming village of eleven hundred residents by 1870 Seattle, even tucked away in the far Pacific Northwest, could not escape the ramifications of a worldwide financial crisis that culminated with the Panic of 1873 and a subsequent economic depression. Lopes’ businesses failed, forcing him to relocate to the new logging town of Port Gamble on the Kitsap Peninsula. Little is known of his life there. Suffering from an affliction then known as dropsy now edema Emanuel Lopes returned to Seattle in 1885. He spent the last ten years of his life as a patient at Providence Hospital. Following his death, Cyrus Walker, superintendent of the Puget Mill Company in Port Gamble, returned Lopes’ body to Port Gamble for burial.

Undated unattributed public domain photograph reputed to be of William Grose

William Grose, or Gross (1835-1898) was born a free man in Washington, D.C., son of a free Black restaurant owner. Grose joined Emanual Lopes in Seattle as the town’s second Black resident in 1861. His wife Sarah Grose and daughter Rebecca became the first Black women to arrive in Seattle. These four comprised Seattle’s Black American population at the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Grose reportedly ran away from home at age fifteen to enlist in the United States Navy. This would have been in 1850, more than a decade before the outbreak of the Civil War, when many officers came from the Southern slaveholding planter class. His physical attributes likely masked his age. A huge man, Grose stood six feet four inches tall and supposedly weighed over four hundred pounds. Following expeditions to the Arctic and Japan, Grose, honorably discharged from the Navy, joined the California gold rush. While working as a miner, he opened an underground railroad helping escaped slaves who had traveled across Panama to make their way up the West Coast to British Columbia. Grose helped establish a settlement of escaped former slaves on the Fraser River.

Returning to sailing, William Grose joined the crew of a mail carrier called The Constitution plying the waters of Puget Sound, aboard which he had a fortuitous meeting with Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens. Governor Stevens encouraged Grose to drop anchor in Washington Territory. Grose opened a hotel and restaurant in Seattle on Yesler Way, called Our House, where he befriended Seattle’s prominent white pioneer families. Grose’s hotel provided lodging for many of Seattle’s Black residents who followed Grose to the city. Grose was known as a generous spirit. He sold his restaurant for $5,000 prior to the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 which destroyed the building along with most of the rest of Seattle’s commercial district. Following the fire, Grose returned the $5,000 to the new owner.

Thanks to his business acumen bolstered by the personal relationships Grose developed with Seattle’s white business elite, William Grose became the wealthiest Black resident of Seattle during the Nineteenth Century. Wealthy enough to purchase in 1882 a twelve-acre ranch along East Madison Street from Seattle pioneer Henry Yesler for $1,000 in gold. Grose commenced selling off parcels of the ranch to other successful Black residents of Seattle creating the northern anchor for what came to be known as the Central District, the center of Seattle’s Black middle class. Following his death in 1898, William Grose was buried in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetary.